On Violence in Broome County: Why is gun violence increasing? And crime not?

That’s a paradox that you won’t hear from local media or elected officials. The stories they bleat at us repeat a fearful line: violent crime is escalating and threatens us all, daily. And people across the county and state clearly have a heightened fear of crime as a result. Sheriffs, police chiefs, and elected officials now amplify this fear to demand we rollback criminal justice reforms and refill emptying jails and prisons. But have criminal justice reforms had this effect, and what do we do?

Bail reforms passed in 2019 eliminated bail for most misdemeanor and non-violent charges. Opponents propose new legislation to grant judges more autonomous power to incarcerate “dangerous” persons and imprison those with substance use and mental health problems. State Senator Frederick Akshar and past Binghamton Mayor Richard David have launched a statewide campaign towards this end, as have current Sheriff David Harder and regional Sheriffs. Rolling back reforms would be accompanied by more funding for police, prosecution, and incarceration. New York’s New Mayor Adams and President Biden agree. Governor Hochul and conservative Democrats, including Broome County Executive Jason Garnar, have conceded and proposed their own 10 point program to rollback recent reforms.

None of these advocates for more incarceration have produced systematic evidence or analysis of the impact of reform to support their legislative proposals. Simply put, the facts and data we have don’t match these fearful visions—as suggested by the seeming paradox between fears of rising crime and actual crime rates. To unpack these contradictions we need to take a straightforward look at crime and violence.

Crime? What Crime?

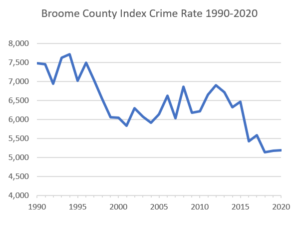

Start with the crime situation. New York State statistics show that index (serious) crime rates for Broome County have steadily declined over the last four decades and actually fell significantly from 2017 to 2020 (2021 county figures are not yet released).

The apex violent crime, murder, is rare in Broome County, averaging but five a year over the last thirty years, including the last five years. Robbery, property theft, burglaries, and motor vehicle theft are also down over the last five to ten years.

One conclusion: the propagated fear of a widespread crime wave due to bail and other reforms doesn’t match the reality we face.

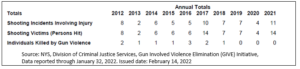

What has notably increased in the last year is the incidence of gun violence. This reverses recent downward trends: state data for the City of Binghamton show that the number of persons injured or killed by gun violence fell from 7 to 4 over 2017 to 2020, but rose to 11 and 14 respectively in 2021.

Broome County is not exceptional here: similar increases have been reported from around the country.

Here we have problem.

Why? Guns, Poverty, Policy

Why is gun violence up? And what might be done about it?

There is little if any evidence that reforms have systematically produced more violent crime. Increases in gun violence have occurred equally in city and states that have and have not adopted bail and related reforms. Data analysis from the Brennan Center concludes simply that “there is no clear connection between recent crime increases and the bail reform law enacted in 2019, and the data does not currently support further revisions to the legislation.” Revised state data are more explicit, confirming that less than 2% of nearly 100,000 released related to the state’s changed bail laws resulted in a rearrest on a violent felony charge while another case was pending. And that’s down from nearly 4 percent from the prior data set.

Would locking up more persons help, as the blustery rhetoric of politicians insists? The clear answer is no. Indeed a good case can be made that jail time increases crime and violence. When people get sent to jail to await trial, overwhelmingly for misdemeanor charges, they most often lose their jobs, apartments and belongings, and become unable to support themselves or their family. Jailing the poor generates poverty, homelessness, and social instability–while the powerful and wealthy post bail and go home from court to their families.

There are many local examples, although few make it in to press. Charged with 87 accounts of bank fraud for kiting 3,600 checks, local billionaire Adam Weitsman awaited trial at home (and was able to afford to settle with a $1 million federal fine and 8 months in prison out of a possible 30 year sentence). As the local Press and Sun-Bulletin editorialized on the case, “the US justice system has long been more lenient with ‘clever businessmen’ than street criminals” (January 16, 2004, p.10) Senator Thomas Libous, charged with a felony account of lying to the FBI, and his son Mathew charged with federal tax fraud, awaited trial at home as well by each paying $50,000 bail. Absent reform, this is how the system works: the poor go to jail and the rich go home. We see these disparities every day in local courts. Bail reform for misdemeanors and non-violent felonies has begun to correct these inequities.

Absent reform, this is how the system works:

the poor go to jail and the rich go home.

Has “defunding the police,” that vilified phrase, led to a permissive crime spree? Despite all the fearful talk by politicians and law enforcement officials, funding for the police, prosecutors, and the courts has increased everywhere. Defunding certainly hasn’t happened in Broome County where the number of deputies and district attorneys and funding for them has steadily increased under both Republican and Democratic County Executives—despite falling crime and a drop in the daily jail count from over 500 local persons to below 300 persons recently. The use of force by police has hardly been hamstrung despite the wave of protests before, during and after Black Lives Matter. Far from it: the number of persons killed by police has steadily risen across the country and set a record number in 2021.

Common sense and work by justice studies scholars point to more plausible forces behind increasing violence and particularly gun violence. In all these areas we need more hard-headed research.

Weapons matter as scholars, police and their critics all agree. A recent profusion of guns into our streets and cities has been noted by many. That’s certainly true locally. Almost ten years ago the County Sheriff reported 23,000 pistol permits alone, and the number has been rising significantly recently. Neither local nor state authorities release data on guns, so the trend is hard to analyze. What we do know is that rising gun purchases nationwide during the covid outbreak have been directly associated with rising violence.

Rising unemployment and poverty, sub-standard wages, and a lack of housing and basic services have long been recognized as correlates of increased insecurity and violence. Broome County is especially susceptible along these dimensions: our poverty rate is the second highest of the state’s 62 counties. Affordable housing is in very short supply as regularly reported by the press and local activists. Homelessness has reportedly increased over 200% in the last decade. And as with incarceration, these factors are directly correlated with not just poverty but race.

And almost all analysts point to the as yet uncertain impact of COVID, which considerably exacerbated the sources and likelihood of conflict. It should not surprise us that even road rage shootings are double what they were prior to the pandemic. As we all know personally, social isolation and the ever-present threat of serious illness and death have heightened the levels of anxiety, anger, and conflict that exacerbate violence. These factors overlap with poverty, coalescing as in the past in poor neighborhoods, where rising levels of violence have often been concentrated.

What is to be done?

What has worked? There is almost no evidence that more policing, already at historically high levels, offers relief. Police invariably enter after shootings and violence, and lack the ability and resources to treat persons in mental or substance use distress. Introducing armed and uniformed persons to confront unarmed persons undergoing a psychotic crisis all too often results in more violence and even death—as occurred in the only incident resulting in the death of a county or municipal officer in near twenty years.[i]

What might alleviate social causes of violence has been an increasing concern nationwide. In both large and small cities innovative projects exist, often with proven track records. Two examples demonstrate the work being done.

Most common and effective have been community-based violence interrupter programs that have spread across the country with documented success. Composed of trusted survivors of youth and gun violence, interrupters unlike police are skilled and trained community members who intervene and reach out to those at the center of gun violence. Interrupters work to address incipient conflicts in their neighborhoods through non-violent means—and provide links to supportive services for housing, education, and employment.

Locality, trust, and respect matter here. Interrupters come from and live in their disadvantaged neighborhoods. This is in stark contrast to local police departments and the county sheriff, who have few members from or live in Black, Latinx, or disadvantaged communities (Broome County has even removed the requirement that county employees including officers live in the county).

Currently police are the first responders,

and the local jail has become the de facto

mental health and substance use treatment center…

A second group of new programs tackle how to work with persons in mental health and substance use distress. Currently police are the first responders, and the local jail has become the de facto mental health and substance use treatment center—a process that cannot but fail to address root causes as indicated by ever-rising substance use and deaths in and outside the jail. Cities across the state and county are increasingly relying trained mental health and substance use response teams which call upon police only in the infrequent cases involving weapons. These projects take different forms, from independent and community-based stabilization centers for those in distress, to teams of street-level mental health and substance use social workers on call and dispatched by 911 and other agencies.

Providing alternatives to law enforcement are critical for persons in distress and conflict—including both victims and survivors. Many in our poorer and most marginalized communities are unwilling to access services directed by or tied to the police—as is current the case in Broome County where current and former police direct mental health outreach services. This reluctance is particularly the case among Black, Latinx, LGBTQ, immigrant and domestic violence survivors.

Moving Forward

In recent weeks, social workers and community activists have pressed the Governor and elected officials to abandon the failed policing and incarceration projects of the past, and turn to long-term, community-centered responses to harm and violence. The recent call from over 100 organizations across the state laid this out clearly: invest $1 billion in community-led gun violence programs and other victim and survivor services. This past month Black-led marchers against gun violence in Harlem demanded the same. We need to abandon the incarceration policies that have failed us in the past and pursue more productive and just policies in the coming years. Wise policymakers and representatives realize we can’t afford to do otherwise.

Notes

[1] The reference here is to the tragic case of Johnson City Officer David Smith confronting James Clark, an unarmed medical technician undergoing a psychotic break outside Wilson Hospital in Johnson City in 2014. Clark was able to seize Officer Smith’s gun and kill Smith; Clark was then shot and killed by Officer Louis Cioci. A 204 page investigation by the police force itself produced no explanation; the family of Clark sued Binghamton and Johnson City for failing to follow protocols and training on how to handle persons in mental distress. Smith was the last local county or municipal police officer to be killed while on duty since 2002 (Binghamton, Johnson City, Endicott, Vestal, Whitney Point, Broome County Sheriff).

A related op-ed was published in the Press and Sun-Bulletin, April 10 2022