The overall impacts from COVID-19 will likely cause significant harm to governmental finances at the local, county, and state levels. Officials at all levels have been warning that the loss of sales tax receipts, casino proceeds, income taxes, and property tax payments could create staggering budget shortfalls. Federal aid, they argue, is the only way to plug the hole without slashing government spending on schools, hospitals, and essential public services.

Is the City of Binghamton well positioned to handle the pending financial crisis wrought by COVID-19? And if so, why? This article intends to answer these two questions, using financial data from 2007 – 2019 and pulled directly from reports and documents produced by the City of Binghamton and available online, including Approved Annual Budgets, Annual Audits, and Annual Update Documents (AUDs) submitted by the City to the NYS Comptroller’s Office. Links are provided to the data source where appropriate. The author is happy to provide documentation of any of the data upon request.

INTRODUCTION: IGNORE THE PARTISAN NOISE, THESE FOUR NUMBERS TELL ALL

When Matt Ryan took office in 2006, the City was nearly broke. All five unions had expired contracts, some of them behind by multiple years. A questionable deal by the former mayor added more than a hundred vacant and abandoned properties to a growing inventory of blighted properties dragging down our neighborhoods. The Hotel Regency was slipping to City ownership, buried under $7 million in debt that was soon coming due. There was a rotary phone in the Mayor’s Office and a 1970s IBM program in the Finance Department spitting out budgets on green and white bar paper. And the former mayor had just hiked taxes by 52% over his final eight years.

It quickly got worse, and never relented.

The City was hit by a flurry of punches: the historic flood of June 2006; a devastating flash flood in November 2006; the Great Recession in 2008 (the worst economic collapse since the 1930s); a traumatic mass shooting of beloved community members at the American Civic Association in 2009; the collapse of a six-year old, 1,500 square foot wall at the sewage treatment plant in May 2011; and unthinkably, another catastrophic flood in September 2011–even worse than the 2006 historic flood–swung through like a knock-out punch.

As I’ve said many time before, the Ryan administration presided over the most traumatic and trying eight years in the history of the City.

Yes, former mayor Matt Ryan raised taxes 52% over his eight years, but that’s the exact amount that former mayor Rich Bucci raised taxes the eight years before (well, only 51.7% to be fair).

But something else happened too.

Under the most trying conditions, the Ryan administration put the City on the strongest financial footing it had been in decades, if ever.

Union contracts were negotiated that respected labor, but ended the sweetheart health insurance plans. The City workforce was trimmed by 10%, and services were consolidated to the County. An award-winning collaboration addressed more than 100 vacant and abandoned properties. The City dodged the $7 million liability of the Hotel Regency by attracting owners that made major investments and turned it into a downtown asset. And the data systems and practices in City hall were revolutionized.

The Republicans have done an exceptional job eliminating this narrative over the years, and I’ve done my best to defend it (admittedly, Team Ryan lost the “PR wars”).

But I don’t want this to be the latest installment of competing partisan narratives, or the stories of contracts, blight, a hotel, and technology. For sure, some folks have legitimate criticisms of the Ryan administration, and I personally have commended some actions taken by the David administration.

As we stare down what local and state government officials are rightfully calling an existential threat to government finances, let’s put the political noise aside and put this simple question to the test: Is the City well positioned to handle the pending financial crisis wrought by COVID-19, and if so, how did that happen?

To answer that, we need to better understand the trends of these four key budget factors: (1) how much the city has in the piggy bank (as defined by the End of Year (EOY) fund balance); (2) the annual amount the City must contribute to the state’s pension system; (3) the annual cost of health insurance; and (4) how much sales tax is coming in, which is the second highest revenue source, after local property taxes.

THE CITY’S PIGGY BANK (SAVINGS)

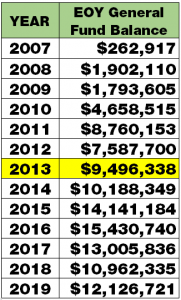

Former mayor Bucci served three terms, from 1994 through 2005. In his final few budgets, Bucci pulled millions from the City’s piggy bank to balance his budgets so he didn’t have to raise taxes even more than he did. He pulled so much that the City was basically out of savings.

Obviously, this isn’t a sustainable solution. To be fair, Bucci faced some really challenging circumstances, but the tactic had serious consequences. For one, Ryan was forced to immediately contend with a major structural budget gap that, with no more savings available to plug the hole, would require some steep tax increases and many other cost-saving measures (some discussed below).

Ryan’s hard decisions had a major impact. As the table to the right shows, based on reports submitted by the City to the NYS Comptroller’s Office, the end of year (EOY) general fund balance was at historic lows near the start of Ryan’s administration. At the close of Ryan’s two terms, the City’s piggy bank savings had been rebuilt to nearly $9.5 million. The NYS Comptroller’s Office recommends that reserves should equal approximately 7 – 10% of the total general fund budget. When Ryan passed the baton to David, the City was already well above that recommendation.

Note that the EOY balance continued to increase under David, and it’s reasonable to ask how David continued to build the savings in the City’s piggy bank.

The answer: it had little to do with David. He was a fortunate benefactor of major trends outside his control, just the right guy in the right place at the right time. Which brings us to the three other key budget factors mentioned at the start of this article.

TWO MAJOR EXPENSES: PENSION AND HEALTH INSURANCE

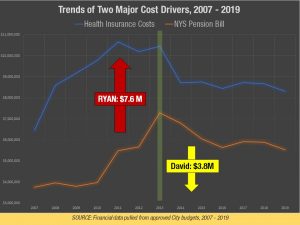

Health insurance and pension costs are two of the biggest expenses in the City’s annual budget, and will significantly influence what a mayor can or can’t do with each annual budget. Don’t take my word for it.

In his 2019 State of the City Message, Mayor David emphasized the impacts of these two major budget drivers: “Health and pension costs have historically been two of the primary factors behind tax increases.”

In his 2016 State of the City Address, Mayor David said, “Over the last decade, one of the primary financial obstacles the City has grappled with relates to mandatory increases in contributions to the New York Retirement System…2014 and 2015 were the first two years in more than a decade in which the City’s pension costs actually decreased.” [emphasis mine]

Surprisingly honest words from Mayor David.

He’s right, of course. If you chart out how health insurance and pension costs have changed over the years, from 2007 to 2019, a very clear story emerges, one a bit different from the political narrative that the Mayor and his partisan acolytes unfairly hammer home every chance possible.

Let’s look at them one at a time.

As David acknowledges and the chart shows, the pension bills skyrocketed following the collapse of the stock market due to the Great Recession. The moment David took office? The bills dropped considerably, again, a trend he honestly acknowledges in his State of the City Address.

It’s important to note that no municipality has any say over pension bills. New York requires that the pension fund is 100% funded, which means when the stock market tanks and the pension fund drops, the Comptroller relies on local taxpayers to make up the difference. David explained this perfectly in a recent Press and Sun Bulletin article (5/16/20):

“David fears the recent market free-fall [due to COVID-19] could mark a return of significantly higher employee retirement outlays in coming years as the New York state comptroller, manager of the pension system, seeks to replenish the pool drained by the Wall Street collapse.”

This is exactly what happened under former mayor Matt Ryan. Following the Great Recession, the stock market collapsed, and the contribution from the City of Binghamton to the state’s pension system exploded, reaching a high point of $7.3 million in 2013, almost double what it was in 2007 ($3.7 million). Remember, this happened at a time when Ryan had little savings to draw upon, because the City’s piggy bank was dangerously low and quickly trending downward due to decisions by his predecessor.

What about health insurance? Again, the costs ballooned during Ryan’s eight years. But see how the costs flatten in 2014, Mayor David’s first year in office, and stay consistent for the next five years? That’s the result of how Team Ryan effectively tackled this challenge. The Ryan administration negotiated fairly but firmly with the five labor unions, and two key achievements relevant to health insurance were eliminating the “cadillac” plan between 2010 and 2011 (approximately) and increasing the contribution rate of new hires. These hard-fought reforms took a few years to generate significant savings, but when they finally took hold, they not only slowed the growth of health insurance, but actually lowered them–and have kept the City’s health insurance bill stable for years.

Taken together, the total costs of pension contributions and health insurance went in two completely different directions under each administration. Under Ryan, these two major expenses shot up $7.6 million. The day David took office, they started to turn around, dropping by almost $4 million in his first six years.

THE SECOND BIGGEST REVENUE SOURCE: SALES TAX

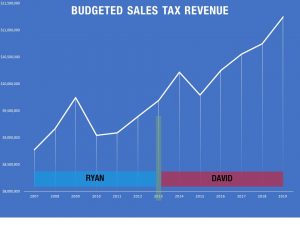

The City of Binghamton, like most other local municipalities in New York, count on three major revenue sources to balance its budget: (1) local property taxes; (2) sales tax; and (3) aid from the state.

While they can lobby and advocate, local municipal leaders have no direct control over two of these major revenue sources: state aid and county sales tax. And aid from the state has been depressingly flat for more than a decade (thanks, Cuomo).

There’s a lot of political history around the county sales tax during this time frame, from 2007 – 2019, but I won’t bother with the details. To keep it simple, a portion of the sales tax collected in Broome by the County has been traditionally split 50:50 between County government and local governments. But when the Great Recession hit, Broome County was desperate to shore up its own troubling finances, and changed the distribution formula of sales tax proceeds so it could keep more (which meant local governments would receive less).

As the above chart shows (based on data pulled from City of Binghamton Annual Budgets), Broome County’s decision to retain more of the sales tax proceeds hit the City hard during Ryan’s tenure, and millions of revenue dollars were lost over the years, until the County finally restored the 50:50 sharing formula at the end of 2014. Again, like manna from heaven (and just like the health insurance and pension costs), David was blessed by changes outside his control. The economy had rebounded, casinos were opening, and the County decided to restore the 50:50 sharing formula, sending the second most important revenue source for Binghamton on a a steady, steep climb upwards.

TAKE THEM ALL TOGETHER: PARTISAN NARRATIVES GO ‘POOF!’

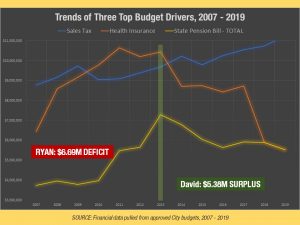

If you combine how these three critical budget drivers–two major expenses and one major revenue source–have trended over the years from 2007 – 2019, then it’s very clear which side of the line you’d want to be on if you had your choice.

The net effect for Ryan was a deficit of nearly $6.7 million. For David, the net effect was approximately a $5.4 million surplus. And to repeat one more time: when Ryan started out, the City was in financial freefall, with less than $300,000 in the piggybank by the end of 2007. When David started out, the City’s piggybank was flush with $9.5 million and trending upwards.

I know for damn sure which years I’d want to be mayor.

I also think we’ve answered the question at the start of the article. Indeed, the City of Binghamton is in a very strong position to weather the financial crisis. For sure, the impacts of COVID-19 to municipal finances will ripple out for years, and absent federal relief, the City will likely need to draw upon much of its savings to weather the multi-year storm. Pension costs will likely increase in the next few years due to stock market volatility, and sales tax revenue will definitely come in far short of expectations. But the City of Binghamton, unlike many other local governments, is in outstanding financial position.

Hopefully, city residents who read this article will have a better understanding of those who deserve thanks, because I’m pretty sure I know who’s going to take all the credit.

LAST WORD: YOU CAN’T HATE RYAN’S TAXES AND LOVE DAVID’S INVESTMENTS.

I remember those last few years working in the Ryan administration, I would occasionally walk down the hall from my office and sit with the mayor in his office long after folks went home. During one of those after-hour conversations, I remember reflecting on the financial troubles we inherited, and how they made responding to unexpected crises like floods and a national economic collapse so difficult. And I remember Matt saying something like, “That’s why we’re going to fix it. So no mayor ever has to deal with what we endured. Whoever steps in after us, Democrat or Republican, we’ll give them a clean slate when it comes to finances.”

That’s the missing piece in a local conversation dominated and driven by partisan narratives, and I want to close with it.

Yes, I suspect Mayor David will continue his cheap attacks on Ryan–he’s too invested in a narrative that has served the local Republicans well over the years. But the financial data from the City’s own public reports, as presented above, tells its own nonpartisan narrative.

And I want to be clear. David wasn’t a benefactor just because health insurance and pension costs dropped and sales tax revenue increased. Yes, those trends helped immensely, but David also benefited from systemic fixes carried out by the prior administration.

During Ryan’s last four years in office, he averaged an annual tax increase of 2.7%, and the tax increase for his last budget was .15%. In other words, when he passed the baton to David, Ryan had finished the work of resetting and and stabilizing City finances to the “new normal” of higher pension costs, higher health insurance costs, and lower sales tax revenue–and at the same time, rebuilt the City’s savings in its piggy bank in excess of what the NYS Comptroller deemed “healthy.” Ryan fulfilled his promise: to make sure the next mayor would be handed a clean slate. He took the political hit for sure, but he also knew it would free the next mayor to serve the city with creativity and flexibility.

But the next mayor was luckier than even Ryan anticipated. Because when those three budget drivers started to reverse course, David had a built-in massive windfall, year over year, to either pass along tax cuts or make strategic investments that he prioritized. He did both, and sadly, took every chance possible to bludgeon the prior mayor and his team of public servants who helped make that possible.

A few things:

- Over the years, Mayor David has called former Matt Ryan’s tax increases “reckless, irresponsible, crushing” and more–even though his former boss Bucci raised tax rates the exact same amount (52%) during his final eight years. But then why, when given the choice, did David pass on tax cuts less than 3% during his first five years? Clearly, as the data shows above, he could have passed on far more significant tax cuts if he had wanted, more like 15-20% over the first five years.

- Instead, Mayor David decided to spend the massive year-over-year surplus he inherited in projects that he deemed critical (and that earned him a lot of political capital). For instance, David took the annual surplus and:

- Expanded the police department, increasing the department’s budget by nearly 20% by 2020 (compared to 2013)

- Committed more than a million of local tax dollars to an aggressive demolition campaign in 2015 and 2016, a run-up to his re-election campaign

- Committed millions of local tax dollars to repave more streets during his tenure

- Made annual contributions to the City’s savings account, and to other new reserve accounts he created (see Financial Note 2 below)

- Withdrew $2.5 million from the City’s piggy bank in November 2018 to fund upgrades at the NYSEG stadium (a process I argued that was questionable and undemocratic, regardless of whether taxpayers thought the investments were of merit)

If it were up to me, my investments would have looked a bit different, and I would have leveraged local tax dollars more effectively, but I don’t disagree at all with the mayor’s decisions to use the annual surpluses to meet community needs. What disappoints me is how disingenuous he’s been about the good work that preceded him, and how the work of Team Ryan and favorable trends that happened outside his control provided him the opportunity to go on a multi-year, multi-million dollar spending spree on roads, demolitions, baseball stadium upgrades, and cops, and to hand-out small tax cuts to rousing applause.

I always shake my head when the Mayor uses his platform to repeatedly advance the partisan narrative: “Ryan disaster, David savior.”

Oh, the partisan silliness of it all, especially when you know the real story.

Look, here’s my point: if you point to the results of David’s spending spree as a “success,” then you can’t also characterize the effective financial stabilization efforts by Matt Ryan, which in addition to many other cost-savings reforms included tax increases, as a “failure.” In partisan terms, you can’t simultaneously praise David as a fiscal conservative wizard and impugn Ryan as a tax-happy liberal. Sorry, but the work carried out by the Ryan administration helped make David’s spending spree possible.

Go ahead, say it with me, “Ryan’s work made David’s spending spree possible.”

Come on, you can do it. I promise. Your head won’t explode.

Tarik Abdelazim served more than seven years under former Mayor Matt Ryan, four years as Binghamton Deputy Mayor and the remainder as Director of Planning, Housing, and Community Development. He embraces the role of a good government watchdog, supports racial and housing justice initiatives in the area, serves on the Broome County Land Bank Board of Directors, and works for a national nonprofit that helps communities tackle vacant and abandoned properties in support of equitable community development. He is a “townie” by birth, lives on the southside with his eight-year old son, and never misses Sunday family dinners.

Financial Notes:

- The number used for the EOY fund balance is the “unassigned fund balance” of the City’s general fund. That’s the amount of money that is absolutely available to cover any unexpected expenses or crises. As an example, suppose you had $1,000 in your checking account, but you know you have a $500 rent check out there, a NYSEG bill of $100 that will paid via direct deposit in four days, and you owe Bob $100 for helping to paint your house–but you don’t know if he’s coming next week or next month to collect. So you don’t really have $1,000 in your checking account to spend freely. You have $300. That’s your “unassigned fund balance,” money that’s not already accounted for or owed to another party.

- Mayor David and City Council in 2018 created new “reserve accounts” for pension costs and health insurance costs, which are dedicated “subfunds” within the general fund that can only be used to cover future increases of the respective expense. He has made transfers from the general fund balance into these reserve accounts, so the City is in an even stronger financial position than the unassigned fund balances in 2018 and 2019 suggest. However, in order to make a fair and accurate comparison across 13 years (2007 – 2019), I couldn’t include these reserve dollars. Still, in fairness and a commitment to accuracy, I wanted to make sure David was credited for these decisions.