by Bill Martin July 4, 2020

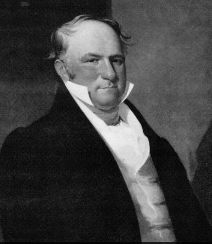

Yet Bingham is dimly remembered today. In the city named after him there is no statue or plaque to mark his place in history. In the mid-1960s his name reappeared briefly when Harpur College was recast as the State University of New York at Binghamton. More recently a new student residence was named Bingham Hall. These are small footnotes to a personage known only to older biographers and local historians who write his history as a far-sighted and vigorous supporter of the American revolution.

What might constitute the meaning and value of Bingham’s achievements depends very much on where one stands. For many, Bingham is the glorious history of a man whose wealth supported the struggle for independence from Great Britain and the principles celebrated in the Declaration of Independence. For others, Bingham and July 4th are marred by the limits of independence and whom it benefited: rich and wealthy slaveowners, eager to shelter their position and wealth from a predatory colonial power.

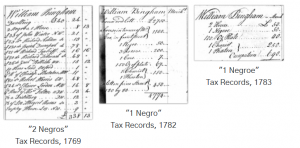

And Binghamtonians should make no mistake here: William Bingham was an owner, trader and exploiter of enslaved Africans as were his more famous friends General Washington and Thomas Jefferson. When he walked the streets of Martinique, he was preceded by an African who held an umbrella over his head.[1] When he left the island, he took a young African with him as a personal servant. When he paid taxes on his property at home, before and after independence, he duly reported his personal slaves:[2]

Bingham’s wealth did not however come from running a plantation with hundreds of slaves like his compatriots. He was more predatory: his head-turning prosperity derived from four short years in Martinique spent capturing and selling Africans and the products produced with slave labor.

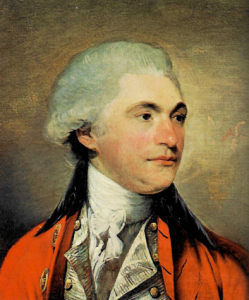

This was his charge from the Continental Congress: to buy and dispatch war supplies for General Washington’s army, to win France over to the colonial rebels’ cause, and to harry and disrupt Britain’s lucrative Caribbean trades. It was the last that provided him a golden opportunity as piracy was legitimized as privateering on behalf of the new nation.

Just how lucrative privateering could be was demonstrated on his passage to Martinique, when his sloop-of-war Reprisal captured a merchant ship flying the Union Jack. Its cargo of rum, cocoa, coffee and sugar were the free fruits of war to be sold and the proceeds shared among officers and seamen. Two more captures followed shortly before the Reprisal reached port.

Bingham learned his lesson quickly. He was soon buying and selling goods on his private account across the war zone while outfitting privateers of his own. Men of his standing were well-prepared by temperament, training and the merchant’s instinct. Bingham’s friend, confidant, and fellow-banker Alexander Hamilton learned his comparably keen skills at King’s college (renamed Columbia College after independence) where his math professor, Robert Harpur of Harpur college fame, set his students the problem of calculating in multiple currencies the value of sugar for the East Indies trade.[3]

Once in Martinique Bingham turned privateering into a commercial operation: he would buy a ship, sign up a captain and crew, and deploy them to attack and seize British shipping. Proceeds from the sale of captured ships and their contents were shared among the captain, the crew, and the outfitter, in this case Bingham. These were extremely lucrative operations, and soon hundreds of British vessels were captured by privateers. The capture of two slave ships in one operation alone in 1777 made Bingham part owner of a cargo of ivory and 284 enslaved men, 45 enslaved women, and 146 enslaved boys and girl. All were auctioned off to great profit.[4]

From such profits came the monies to fund Bingham’s life after his return home, from founding the first national bank to the 1786 purchase of the 36,000 acres that would constitute the town of Binghamton, the buying of 340,000 acres in central Pennsylvania in 1792, and eventually the control over 3,000,000 acres in Maine.[5] His mansions and luxurious lifestyle were legendary.

William Bingham never set foot in Binghamton. His land agent in the area, Joshua Whitney, would name the new town in his honor. It was a slave-holding community. Whitney, no less than Bingham, fully believed and profited from slavery: he bought and owned Black men and women, including a young woman Elinor, his coachman James Patterson, and George and Phoebe Dorsey.[6]

*******************

On July 4th 2020 flags celebrating the founding of a new nation fly proudly all over the city. On my block they include a militia flag and a Black Lives Matter flag. In this contested climate we might pause and ponder the meaning of freedom embodied in the historic and celebrated names of our cities, towns, schools, and streets. To paraphrase Frederick Douglas we might ask, as we struggle to realize that Black Lives Matter: what to a Black person is the 4th of July? Douglass’ challenge remains in front of us: “a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim.”[7]

Endnotes

* Note: this essay will be updated and extended after libraries and archives reopen.

[1] Robert Alberts, The Golden Voyage: The Life and Times of William Bingham, 1752-1804 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1969), 39.

[2] Brooke Krancer, “Miscellaneous Trustees, Slave Ownership, William Bingham,” Penn & Slavery Project, Slave Ownership, accessed June 23, 2020, http://pennandslaveryproject.org/exhibits/show/slaveownership/earlytrustees/misctrustees.

[3] Sharon Liao, ““A Merchants’ College:” King’s College (1754-1784) and Slavery,” Columbia University and Slavery, accessed July 4, 2020, https://columbiaandslavery.columbia.edu/content/merchants-college-kings-college-1754-1784-and-slavery.

[4] Alberts, The Golden Voyage: The Life and Times of William Bingham, 1752-1804, 52, 485.

[5] Alberts, 228–29.

[6] Marjory Barnum Hinman, Bingham’s Land: Whitney’s Town (Binghamton NY: Broome County Historical Society, 1996), 112.

[7] “Frederick Douglass Speech,” accessed July 4, 2020, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4h2927.html.