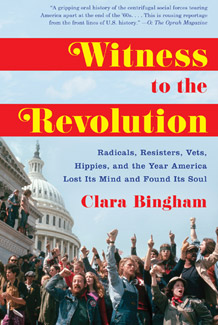

Witness to the Revolution: Radicals, Resisters, Vets, Hippies, and the Year American Lost Its Mind and Found Its Soul by Clara Bingham

Review by Andy Piascik

The primary focus of Witness to the Revolution is the movement against the war in Vietnam. There’s a great deal about the white Left as well as the counterculture and nothing about free jazz, DRUM, AIM, Stonewall or Black Arts. This was a conscious choice. The author explains in an Introduction that Witness to the Revolution is “a selective history” and the book “touches only lightly on the black experience, feminism, and the music scene” because there “just wasn’t room enough in one book.”

Even within that dramatically reduced landscape, Bingham covers a great deal of ground. Many of the seminal events of that one-year period are explored in depth: the Chicago Conspiracy Trial, Kent State, the Resistance, the extensive activism at the University of Wisconsin up through and including the bombing of the Army-Math building, Woodstock, Jackson State, the expose of the massacre at My Lai, Altamont, the Pentagon Papers and more.

Vietnam Vets

Some of the best sections of the book are the stories of the Vietnam veterans who came home and built organizations in opposition to the war. They did so as they often struggled with serious physical and psychological problems while having to live the rest of their lives with memories of atrocities they observed and sometimes participated in. As the interviews reveal, some vets found a degree of healing through activism. Others expanded popular awareness of the true nature of the war by shedding valuable light on war crimes by way of investigative reporters like Seymour Hersh.

Throughout, Witness to the Revolution repeatedly underscores how much vitriol some had to endure as elites attacked both the messengers and the message in the student, vet, Black Power and anti-war movements. Even as late as 1970, when many in the upper levels of government, business and planning had concluded that Vietnam was lost, those who showed that the war was not a righteous cause gone awry but consistent with U.S. foreign policy different only in scale were spied upon, harassed, imprisoned and killed.

Popular Power

As elites today move dramatically to make dissent ever more costly and dangerous, it is inspiring to read of the courage and endurance of those from an earlier time of discord. Fundamental to the success in stopping the war as well as resisting attempts to suppress dissent were the existence of massive movements of a galvanized population that was in many ways at war with its own government. One of the book’s biggest strengths is that the power of the collective Movement is always present even when it’s not front and center. And while Witness to the Revolution was published before the ascension of Trump, the thread linking the popular power of the time to the tasks we confront today is inescapable.

There are anecdotes and surprises both amusing and moving. It’s hilarious in the extreme, for example, to imagine Mick Jagger’s reaction to the vision some had of the concert that became Altamont, as recounted by Peter Coyote, as that of a collective experience where the Rolling Stones would be one of five acts performing simultaneously on separate stages. We also hear poignantly if indirectly from Stephanie Fassnacht, the widow of Robert Fassnacht, the graduate student killed in the Army-Math bombing. Bingham also provides important history of organizations and efforts such as that of the Diggers that deserve more attention and which may stimulate greater exploration by others.

Bingham’s introductory qualifier notwithstanding, it is still unfortunate that she excluded important pieces of the history of that time. This is especially so since she devotes so much space to the sorry tale of the completely marginal Weather Underground. Lots of people worked to stop the war in Vietnam even if that may not have been the specific focus of their activism; couldn’t we have heard something from some combination of Elizabeth Martinez, Mike Hamlin, Frances Beal and Dennis Banks? Maybe a little something about the August 29th Chicano Moratorium, which was within the time frame Bingham covers and drew upwards of 25,000 people to the streets of Los Angeles?

Instead we once again get page after page of Mark Rudd, Bernardine Dohrn and Bill Ayers. Rudd’s regrets and likening of himself to a police agent are to his credit; too bad the Weather Underground’s story couldn’t have been left at that and some space been granted to the original Rainbow Coalition, say, that was working at the same time and in the same city where Rudd and his comrades were carrying out the senseless Days of Rage. Juan Gonzalez is quite visible and not difficult to locate; wouldn’t it have been more valuable to hear him on his experiences both as a student activist at Columbia and as a leading figure in the Young Lords?

Stories That Need to Be Heard

Witness to the Revolution contributes a great deal to our understanding of the movements of the 1960s despite this weakness. The book gives voice to people from that time whose stories absolutely have to be heard and amplified as elites continue to distort, ridicule and de-fang the movements of opposition while also re-writing history, such as in the Pentagon’s recent official account of the war in Vietnam. The importance of recording the stories of movement participants is underscored by Bingham’s mention of those subjects who have died since she interviewed them, a number that has increased since.

Lessons for Today?

Among the lessons of the book that seem to apply to 2018 are, one, the need to utilize a variety of tactics; two, the need to resist and organize against as many of the attacks coming from the Trump Administration and the ruling class in general as is possible; and three, the need to establish alliances between those working on all of the many issues.

On the first point, we must continue to organize the kind of rallies, protests, strikes, and sit-ins that have been much in evidence since Trump’s election, right on up to actions that may include mass civil disobedience. The diversity of tactics including the willingness of many thousands to risk arrest or even violence at the hands of the police is one of the biggest strengths of the activism Bingham covers in her book. Similar efforts today should be supplemented by holding public officials accountable such as has been done at town hall meetings throughout the country as well as by challenging Trump allies in elections with candidates, preferably people who are a part of the emerging movements but who at minimum reflect the views and values of those movements.

That we need to be present and organizing around all of the many issues is probably self-evident. The ever-growing movement in opposition to police violence against black people and the resistance at Standing Rock against the North Dakota Access Pipeline can serve as examples of how people from different parts of the country, different races and whose main activism may be on some different issue, can come together as needed to oppose a particularly dangerous threat. It wasn’t enough, not nearly enough, but that can change, just as happened over a few short years in the period covered in Witness To the Revolution. Since ecological collapse and nuclear war are among those threats, the sooner we can get more of what we need up and running the better. The recent coming together of a large number of groups tackling a wide spectrum of issues throughout the country in a new coalition called The Majority is a positive development in this direction.

Given the scale of the trouble we face, we need more books like Bingham’s. Such resources will be of great value as we confront challenges the only antidote to which is the construction of popular power on a mass scale. Witness to the Revolution is testament to how much such popular power can accomplish even in the most daunting circumstances.

Andy Piascik is an award-winning writer whose most recent book is the novel In Motion. He can be reached at andypiascik@yahoo.com.